The Role of Simulation Software in Yacht Racing

The Team Helping Land Rover BAR to #BringTheCupHome: Interview with Cape Horn Engineering

Cape Horn Engineering was founded in 2007 with the vision of using the best available CFD tools for the design of racing yachts. They have been involved in several America’s Cup campaigns and their designs have dominated the Around-the-World Volvo Ocean Race for almost a decade, winning three times in a row, with ABN Amro (2005/06), Ericsson Racing Team (2008/09) and Groupama Sailing Team (2011/12). Cape Horn Engineering is proud to be involved in the design team at Land Rover BAR, the British Challenger for the 35th America’s Cup in Bermuda 2017, whose aim is to #BringTheCupHome, where it all started in 1851.

With the company in its second incarnation as a partnership between original founder Rodrigo Azcueta and naval architect and marine engineer Matteo Ledri, the team has successfully expanded their range of activities within the maritime sector to commercial ships, large superyachts, and more recently the renewable energy market.

Deborah Eppel, Technical Marketing Engineer at CD-adapco, talks with Rodrigo Azcueta, Matteo Ledri and Elisabeth McLean about the role simulation software has played in the very competitive field of yacht racing, and how it has helped them discover better designs. Faster.

Tell us about yourself. What attracted you to CFD?

Rodrigo: I come from a family with a very strong maritime background. Both my father and grandfather were navy officers. I started sailing at a young age and discovered a passion for racing boats. For that reason, I studied Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, first in Argentina and then in Hamburg, Germany, where I also completed a PhD specializing in CFD applied to yachts and ships. As a student, while working in towing tanks, I realized that computers and simulations were going to take over from the physical models, so I decided to focus on the newest simulation methods. Computer simulations for ships had existed for a long time with simplified theories, but the new methods based on RANS CFD opened up a whole range of new possibilities with far more precise flow analysis than had been possible until then. This was more than 15 years ago, and I was in the right place at the right time: I found myself pioneering the field of RANS simulations with free surface for floating bodies, i.e. simulations of boats or ships free to move on the surface of the ocean under the effect of external forces like wind or waves. In 2002, I felt that the timing was perfect to apply those innovative methods for the design of high performance yachts such as those used in the America’s Cup and to fulfill my dream of working for a team. I presented my work in Auckland (NZ) at a conference in the context of the America´s Cup and got the attention of several yacht designers who offered me to work in their teams. This was the beginning of my current profession.

Matteo: Being a sailor since I was a kid, I think it was natural for me to study Naval Architecture and being attracted to fluid dynamics. I love studying and understanding how a boat interacts with air and water. CFD allows this, and does it much better than a towing tank or a wind tunnel. You can predict the forces acting on the system and also visualize wave patterns, streamlines and pressure distributions on all the components. And if you have a crazy idea, you can test it quickly without building a physical model. Cape Horn Engineering is a company doing exactly all of that at the highest level. I had studied Rodrigo’s publications at university and now I am proud to be a partner with him at the company.

Elisabeth: Flow dynamics is such an interesting field to get involved with. The marine environment is affected by engineering decisions at all levels — a well-positioned exhaust duct will not create any discomfort for the guests on a motor yacht and designing the fastest yacht will win you races. CFD is a great tool to understand and predict marine performance because it gives you both quantifying data such as drag on the hull, and visual data to further understand the flow behavior. Cape Horn Engineering is a company with a wealth of experience in designing winning race yachts, and since I have joined the team I always have something interesting to work on at my desk.

What kind of problems are you trying to solve with STAR-CCM+?

Elisabeth: There are three main areas we work on: sailing yachts to increase the yacht performance and help our clients win races, shipping to cut fuel cost or to improve comfort on luxury motor yachts, and renewable energy to harvest most of the wind power.

Do you have a few specific examples you could tell us about?

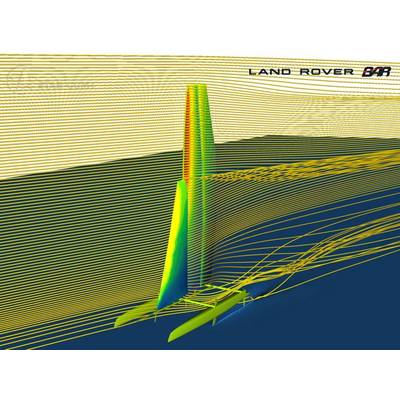

Matteo: In the design of an America’s Cup racing catamaran, there are a lot of components involved: hydrofoil simulations with motions and free surface, aerodynamics on wing, sail and all the platform fairings, fluid-structure interaction, cavitation modeling, laminar/turbulent transition, and many more. STAR-CCM+ allows us to do all of the above with the same tool, streamlining the workflow with powerful automation capabilities.

Elisabeth: For the daggerboards – the foils, the fluid mechanics of lift is paramount. Sailboats are generally far more complex than an airplane which is immersed in only one fluid – air – whilst the foils on the boats are piercing through the free surface between air and water. The design aspect of lifting surfaces within the presence of a free surface is still a new field of fluid mechanics. Furthermore, America’s Cup boats have a rigid wing with a flap element instead of a traditional fabric sail. Adjusting the angle between the two elements of the wing changes the deflection of the airflow for more force to be generated. We are aiming to design the most efficient wing whilst giving the wing trimmer as much control as possible.

How did you end up choosing CD-adapco as your CFD solution?

Rodrigo: We have had a long association with products from CD-adapco. It started 20 years ago when I was at the University of Hamburg and started using COMET, one of the predecessors of STAR-CCM+. I was sharing the same offices as the developers of that code and had to write my own routines in FORTRAN to make the solver do what I wanted it to do. Initially, we could not model the interface between water and air, the so-called free surface. But then, a Volume of Fluid method was implemented in COMET and I was the beta tester, and for sure the first researcher to use it for yachts. COMET became in the following years the tool of preference for solving ship flows with free surface and started to get more and more users worldwide.

After a long time using COMET, I switched to using STAR-CCM+ and haven’t stopped using it since then. In my view, STAR-CCM+ is the best code in the market, especially for applications involving ships and free surface flows.

Matteo: STAR-CCM+ DFBI solver together with overset grid technology is perfect to simulate equilibrium conditions on a flying boat where large motions are involved. Everything can also be automated, making it easy to perform parametric studies. The java API are extensive and well documented and the support is quick and helpful. When we joined Land Rover BAR at the beginning of 2014, we knew that STAR-CCM+ would be our first choice. But it’s always good to keep an eye on other tools in order to find the best one for the job, so we completed an extensive evaluation of different products. At the end of the day, we had a clear winner in the efficiency and flexibility of STAR-CCM+, the new optimization package Optimate, and the outstanding technical support from CD-adapco.

What impact has CFD had in the marine industry? Why do you think the industry is so reluctant to move away from model testing?

Rodrigo: In my view, the marine industry can benefit more than any other industry from CFD simulations. This is due to the size of the ships, and the fact that they move at the interface between water and air. Planes are big as well, but they fly in one medium only. Cars are small and can fit inside a wind tunnel. But ships are huge and float on water, and because of the physics involved, it means that the force similarities between the model at scale and the real ship cannot be achieved in a towing tank. That’s why a test in a towing tank is very tricky and is based on a lot of assumptions, empirical formulations and experience. Today with CFD, this problem is eliminated since we can model the ship at full scale.

The shortcomings of towing tanks are more evident in the case of sailing yachts. Yachts create a large lateral force compared to the resistance. In addition, yachts sail in a wide variety of conditions, drifting sideways, heeling over, pitching and at many different speeds. For these reasons, testing sailing yachts in towing tanks is much more difficult than testing motor ships. I, and a few others, recognized this situation many years ago and campaigned for using simulations only in the design of yachts. Nowadays, I don’t think there is any racing team that would use towing tanks instead of CFD for the bulk of their design.

In the case of commercial ships, the industry is very conservative. And since they deal with products that are hugely expensive to build and operate, they prefer to rely on the experience of towing tanks for their final designs to make sure that they meet their clients’ requirements.

The main problem with CFD is that it has become very easy to produce some sort of results and nice flow visualizations. While good towing tanks with enough experience to predict ship performance within a few percent error do not exist in a large number, maybe 20 worldwide, new so-called CFD experts arise every day and claim to predict performance within 1 percent precision. For this reason, it is crucial to choose a CFD service provider carefully.

Elisabeth: Another advantage of CFD compared to the towing tank is that CFD can investigate the forces on each component of the ship or yacht, the hull, appendages, the sails, and the propeller. It can also take into account complex physical phenomena like cavitation, the transition of laminar to turbulent flow, spray and wave of foils piercing the free surface, the deformations or fluid-structure interaction, flow separation, stall and reattachment, and the dynamic behavior of the boat in the environment.

What kind of problems are still challenging for CFD?

Rodrigo: One of the main challenges we have been facing all these years is what we call numerical ventilation, especially for planing hulls. For instance, in a motor or sailing boat, the free surface gets smeared and unphysical ventilation (air bubbles) below the hull is observed. This is a typical problem of the Volume of Fluid method. When numerical ventilation occurs, not only is the friction resistance not well captured, but also the stagnation pressure at the bow cannot build up and the bow wave is smaller than it should be. The resulting forces can be in error by as much as 50 percent. After dealing for quite a long time with this difficulty, we now have found a solution that works and are confident that our simulations are quite accurate.

Considering that all racing teams are using CFD, what do you think will be the deciding factor in terms of who wins?

Matteo: We are working in a highly competitive environment, pushing the envelope in all areas of the design, so we need to provide a quick and reliable CFD solution for the production of performance data and, at the same time, work on R&D to develop tools and techniques that will be key to improve the design in the future. The key part is finding the right balance between producing results and improving them through R&D, and between accuracy and speed. It’s essential to be accurate enough to drive the design in the right direction, but it’s also very important to deliver quick results so more design variations can be tested.

How do you combine your personal experience of sailing with CFD simulations?

Elisabeth: We are experienced sailors and that gives us first-hand knowledge about the product we are designing, and we understand the physics that the yachts are exposed to. CFD enables us to use our experience and understanding to explore a large design space and/or to focus on small details, the sum of which makes for a winning boat.

How is it to work for Land Rover BAR?

Rodrigo: Land Rover BAR is a fantastic team made up of great individuals and team players. We at Cape Horn Engineering are really proud of having embarked on this journey with this team. The whole team is under the same roof here in Portsmouth in this spectacular headquarters. Technological advances have always been at the heart of the America’s Cup, and here at Land Rover BAR, we have the proper CFD resources in place to explore innovative designs to get the edge we will need to win the Cup and bring it home.